The Story is the Story: On Management #40

The holidays were fun and long, and I’m glad we’re all still here.

Please allow me to be the last person to send out a 2019 recap, and a little something new.

Thank you for inviting me to your inbox.

2019 in Review

The newsletters:

Are norms really normal? (P.S.), Ready for your intervention? (P.S.), Minimum Viable Passion (P.S.), Always be coaching (P.S.), and Ask (better) questions (P.S.)

The Soundcloud playlist for my 2019 audios is here. I also appeared on Ashley Milne Tyte’s The Broad Experience, episode 140; we talked about coaching.

Newsletters for supporting members (some are still paywalled):

Dead (White) Men Talking, Audio Transcript, CV Harquail on Feminism and Business, Wheels within Wheels, Audio Transcript, Jane Watson on the Toronto Tech Study, So I've been thinking, Audio Transcript: Fobazi Ettarh on Vocational Awe, Problematics, I Kind of Want A Revolution, Audio Transcript: Ask (Better Questions), The Women's March, and Burnt(Out) Offerings.

If you’re Deaf, hard-of-hearing or otherwise desire an audio transcript, I will make one available upon request.

The story was the story

The central drama of the workplace is when a manager and team members fail to agree on what needs to be done. Or so I say.

In the early ‘10s, I started noticing storytellers speaking at conferences. Giving workshops. Writing books. Talking TED.

I wondered, what if I were to frame the central workplace drama as, actually, a narrative problem? Would it mean that managers should be better storytellers? Possibly correct, I guessed. I thought about hosting a storyteller for a workshop.

And yet something didn’t quite sit right with me, and I decided that storytelling wasn’t the right intervention. I moved on.

Fueled by abundant capital, the decade wore on. An emerging narrative gained strength: lots of storytelling said that organizations should grow, fast. Collateral damage be damned, go for Total Market Domination.

And, It Will Be Worth It.

Almost every blitzscaling org that I have seen up close has a lot of internal unhappiness. Fuzziness about roles and responsibilities, unhappiness about the lack of a clearly defined sandbox to operate in. “Oh my God, it’s chaos, this place is a mess.” The thing that keeps these companies together…is the sense of excitement about what’s happening and the vision of a great future. Because I’m part of a team that’s doing something big…the pain will be worth it.”

Reid Hoffman quoted in Blitzscaling, by Tim Sullivan at Harvard Business Review

We were promised flying cars, but that was a long time ago.

More recent promises include driverless cars, and worlds where no one a) feels alone, and b) ever has to say goodbye too soon.

Um.

Who’s the narrator?

“Brash young creative geniuses KILLING IT” gave way in 2019 to “Bad Apples have been running things around here, but we’re gonna fix it now.”

So far, “unsustainable business model” is not a terribly popular story.

In 2016, Reid Hoffman told a story: “You fix the things that will get investors to give you more cash.”

So, in a Bad Apple’s wake, do you fix the company, or fix the story? Both? And who’s telling the story anyways?

After the 1987 stock market crash, an acquaintance reported that her stockbroker boyfriend felt guilty. As the market tanked, he had profited by executing sales trades. For clients who had originally bought the stock from him.

Of course, this was his job.

When an idea, company or person gains momentum, there’s all kinds of media on the buy side. They’re also there on the sell side, when things crash and burn.

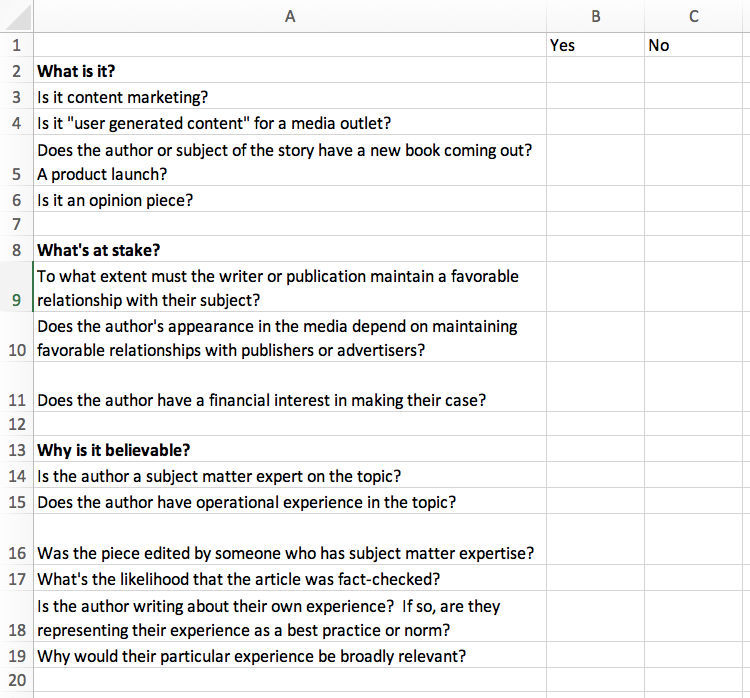

And as we click and share, we make the market. Yes, there are reliable narrators. We still have to interrogate them.

Look for the author

When it comes to the narratives on work, we don’t see an author. We see beliefs.

That you should learn to “code.” Hustle.

That it’s ok to work full time and not be able to support yourself. Ok to be paid less than the guy next to you.

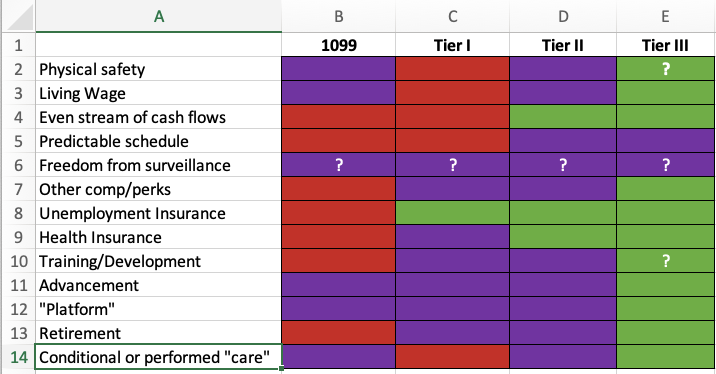

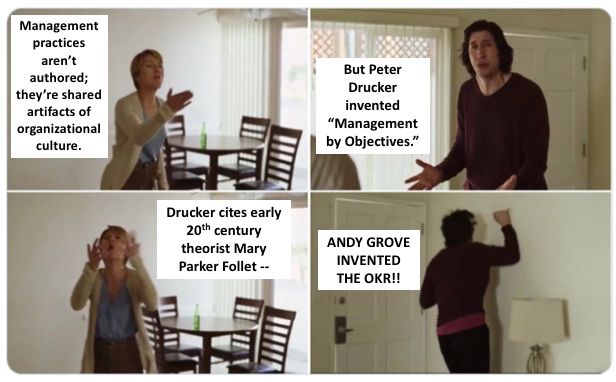

That very particular great men (even men’s men) have been people management innovators, rather than observers and adapters of common practices that are the accretion of generations of knowledge and practice, for better and for worse.

Like the actions of God — or A God — or the market — we only see outcomes.

Is #MeToo a battle between author and narrator?

Optimistic Me: Maybe #MeToo is a triumph. Finally, here are the stories of some who have been silenced.

Cynical Me: Don’t just sit back and watch the story go by. So many problems with our narrators, gatekeepers, and people who are meant to ensure justice.

There’s a lot of work to do.

Because we’re seen this movie before, too.

If you’re here, I’m guessing you’re a reader

Here’s another story: The Liberal Arts are Dead.

Maybe students should securitize themselves in exchange for vocational training. Say, learning to program computers. The sort of on-the-job training that their parents completed on their employers’ dime and time.

In the face of crappy stories, our best offense may be the ability to critically engage a text — whether it’s this newsletter, your CEO’s pitch, or a story in the media outlet of your choice.

Long live the liberal arts.

Who gets to tell stories — about tech?

Lizzie’s literary genius rests not just in her acres of quotable one-liners…but in her invention of what was really a new form, which has more or less replaced literary fiction — the memoir by a young person no one has ever heard of before. It was a form that Lizzie fashioned in her own image, because she always needed to be both the character and the author.

Author David Samuels, quoted in Elizabeth Wurtzel, ‘Prozac Nation’ Author, Is Dead at 52

An entry-level employee spends a few years in a few tech/startups. Then she writes a singular memoir.

Anna Weiner’s Uncanny Valley: A Memoir (library) (Indiebound) brings a young woman’s narrative voice to a world largely peopled, authored, and narrated by men.

Weiner sees “the ecosystem” and its structures. Gently, dreamily, deftly, she opens them to wider scrutiny.

And she gets it. The -preneurship, the meritocracy, the employee-number-upsmanship.

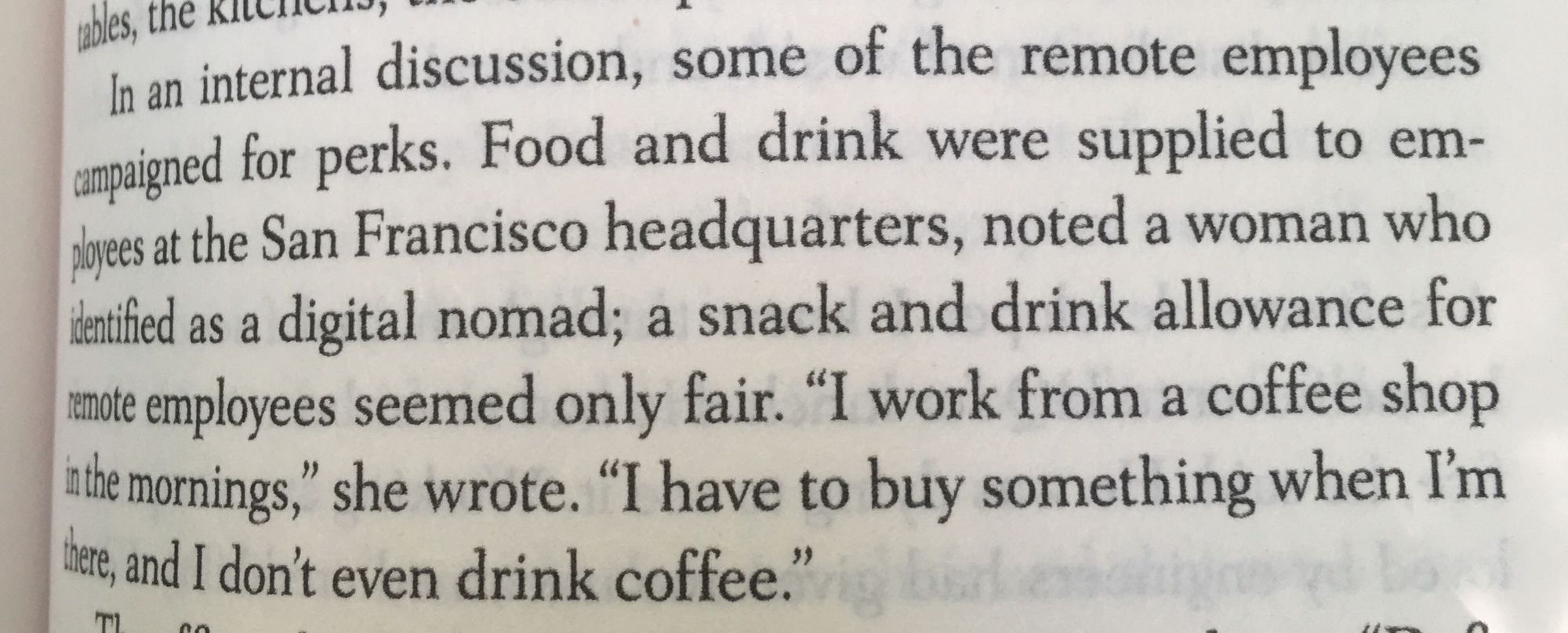

One passage stopped me short. Then, I took a screenshot and immediately slacked it to someone I worked with a few years ago.

We had seen this movie together. It was called Snack Monetization. Or maybe it was called Snacks as Comp. Snack Entitlement?

(I’d share my former client’s response, maybe, if I hadn't signed an NDA.)

In the months since I read Uncanny Valley, it has stayed with me. It’s a different story from other literary memoirs I’ve loved. Weiner is not eclipsing her origin story, and/or healing from trauma.

She’s not a victim, survivor, or hero: she’s a passenger on the luxury bus we call Tech. It’s navigated and driven by young men. Gas and upkeep, to a point, are funded by older men.

As readers, we’re along for the ride.

Anna’s writing about what it means to belong and grow at work, and what it means to wake up to the story.

Again and again, reflecting on Uncanny Valley brought me back to Lost in Translation. So I watched it again.

Recent college grad Charlotte is a guest in a luxe Tokyo hotel, traveling with her husband John, who’s there for business. Left to her own devices as John works, Charlotte connects with a weary middle-aged film star, Bob.

I can't tell you how many people have told me that (they) just don't get "Lost in Translation." They want to know what it's about. They complain "nothing happens." They've been trained by movies that tell them where to look and what to feel, in stories that have a beginning, a middle and an end.

“Great Movie: Lost in Translation,” Roger Ebert

Trapped in structures constructed by, and for, the privilege they enjoy, Bob and Charlotte exercise little agency.

Their souls are starving; it’s time for karaoke.

Roger Ebert’s piece on Lost in Translation is lovely and flawed: Ebert sees Bob at the center of the story. Director Sofia Coppola is playing a bigger game, though, radically placing Charlotte’s perspective on equal footing with Bob’s.

If “business memoir” existed as a literary genre, the template would be a Great Man’s success story, a tale of overcoming. Or maybe vindication.

Male voices infuse the narrative groundwater of business, tech, and work.

To me, they’re shouting so loud that my first drafts of this very piece led with an exegesis of a man’s 1980’s memoir of his entry-level years in the newly-hot industry of that age, finance.

As I edited, news broke about Elizabeth Wurtzel’s death. I remember her from when we were both young. She was Controversial; the media loved-hated her.

I hadn’t bothered. Or maybe hadn’t deigned.

Jumping from Wurtzel’s obituary, to pieces about her, and by her, today I see a contemporary who spoke plainly about both hard and frivolous things. A woman who didn’t appear to care what people thought.

I berated Current Me. Had Younger Me allowed internalized sexism to stop her from reading Elizabeth’s work?

Ultimately, I had to forgive Younger Me. She desperately needed to be seen as Likeable — by the right people — to maintain her tenuous purchase on the next rung of the corporate ladder. In heels and a pencil skirt.

I didn’t have time for someone who didn’t care whether we liked her: I couldn’t afford to…relate.

(Lost in Translation’s) cinematography by Lance Acord and editing by Sarah Flack make no attempt to underline points or nudge us. It permits us to regard.

“Great Movie: Lost in Translation,” Roger Ebert

Mary Karr says, “In some ways, writing a memoir is knocking yourself out with your own fist, if it’s done right.”

In Uncanny Valley, Anna Weiner doesn’t bash or cheerlead for tech, or herself.

Instead, she permits us to regard.

(Disclosure: I requested and received an advanced reader’s copy of Uncanny Valley, which comes out on Tuesday, January 14.)

Continuity

So many endeavors and questions don’t lend themselves to the boundaries of a year, a review cycle, or even a decade. I’ve been thinking about continuity.

Last year I put a few questions out here:

- How am I responsible for unintended consequences?

- What am I not seeing, and how can I see it? Do I see anything that I can render more visible?

- How can we develop and advance a better understanding of business history?

I’ve spoken indirectly to these questions, and there’s more to be said.

I’ll come back to this, along with another question — why does any particular organization need to persist?

New for 2020

There’s a certain “circling the drain” quality to viral workplace stories.

Commentary pours in. Wise, inane, comedic, otherwise. Then, it surrenders to gravity, volume, and the shape of the bowl.

In June-ish, I wrote and posted something every day behind the paywall. When I stuck my toe in the water on a recent viral story, I thought back to that exercise*.

For 2020, supporting members will get my occasional Sunday morning “warm takes.” They’ll be short and sweet, like one that I just unpaywalled.

Later this month, I’ll raise the subscription price for new supporting members — if you’re already a member, nothing will change.

*(Here’s a June 2019 piece I unpaywalled, about WeWork.)

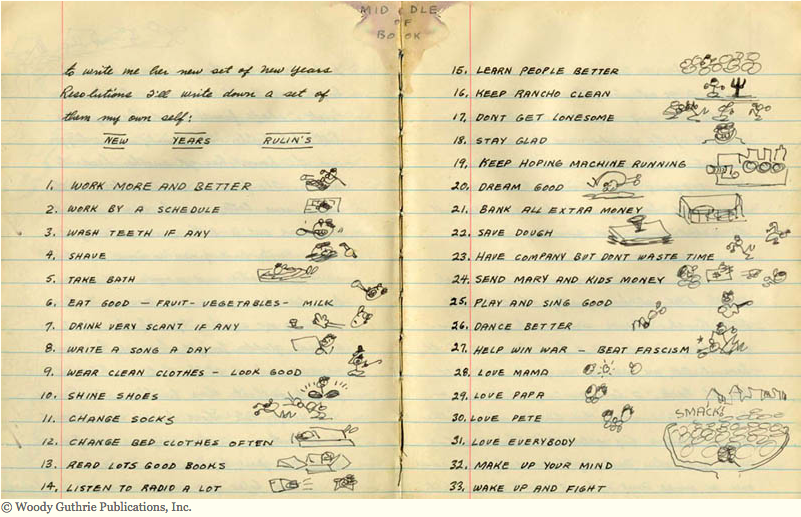

New Year’s Rulin’s

“32. Make up your mind.” Thank you, Woody Guthrie.

Many thanks to everyone who has read, shared, or contributed to my newsletter.

I love receiving email — bits and pieces of our conversations wind up in the compost of my mind, and always make what I share here smarter and better. So if you have feedback, questions, or suggestions, please use this link to send me a note.

Thank you so much for reading the newsletter, and happy new year to you and yours,

P.S. If you’re reading this online, it’s been polished since I sent it out by email. Not to perfection, lol.

Roger Ebert’s review of Groundhog Day correctly places Bill Murray’s character at the center of the story. #pedantic