Minimum Viable Passion: On Management #37

Thank you for inviting me to your inbox!

Welcome to new readers. And hello, librarians who are here because my audio guest, Fobazi Ettarh, shared the promo for our conversation. (Thanks, Fobazi.)

Vocational awe and (short)changing the world

And if you don't buy into it, if you're one of those people who say, “Well wait a minute. Yes, my job is important. Yes, I really care about my career, but I also want to have a family. I also want to engage in a robust personal life.”

Then…you become someone who is seen as less effective, solely because you’re quote-unquote “less passionate” about your job. And if you're seen as less passionate, and therefore seen as less effective, well, then there's no room for professional growth.

Fobazi Ettarh in conversation with me On Management #37

Fobazi Ettarh joined me to discuss narratives about changing the world and passion in the workplace. And a concept she named, and is exploring: vocational awe.

Is an organizational mission or profession so important that it’s beyond criticism?

There’s more from Fobazi in our audio. I edited our converation for length and clarity.

Fobazi’s work on vocational awe is informed by her experience as an academic librarian.

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire. Where there’s a workplace narrative about being mission-driven, or passionate, look for vocational awe. I see it in tech and startups, too. In not-for-profits.

At best, mission is a roadmap to a goal, not a license to treat people poorly. Passion is a feeling, not an achievement. Also:

Passion, devotion, and awe are not sustainable sources of income.

Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves, by Fobazi Ettarh

You’ll find more of Fobazi’s work here:

- Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves

- Becoming A Proud “Bad” Librarian, and more, is at her blog.

- Killing Me Softly: A Game about Microaggressions

Fobazi Ettarh is the Undergraduate Success Librarian at Rutgers University-Newark. She specializes in information literacy instruction, K-12 pedagogy, and co-curricular outreach. Her research interests include equity, diversity, and inclusion in librarianship, and the ways in which societal expectations and infrastructures privilege and/or marginalize certain groups.

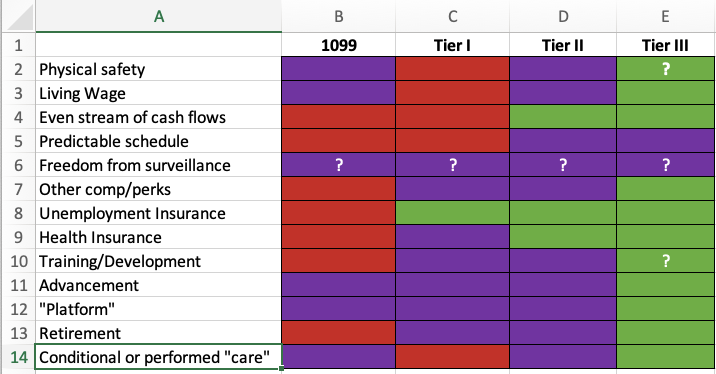

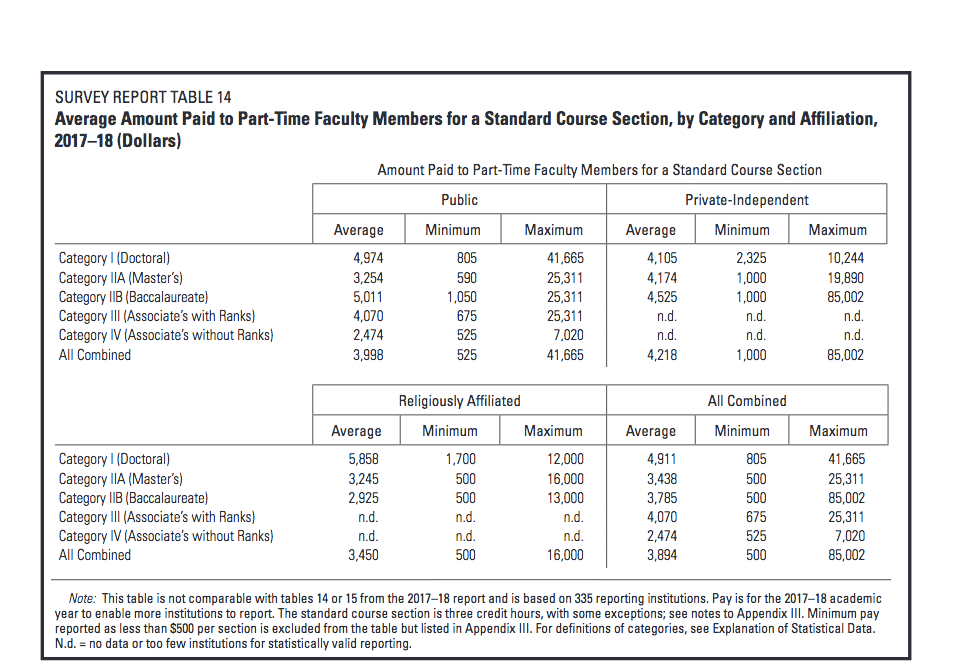

In the audio, I wandered into a side point about non-tenured university professors, and commented that some adjunct professors in the NY area are paid $1500 to teach a semester-long class.

I searched high and low to source the figure I cited, and I couldn’t.

Data from the American Association of University Professors indicate that I may be lowballing the number for NYC; it’s hard to tell.

Across all responding institutions, the average pay for a part-time faculty member teaching a three-credit course was $3,894—but the pay rates spanned a huge range.

The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession, 2018–19 (See also, its Appendix III.)

The mode would have been a good statistic to report here for context, but I digress.

My point stands — many teachers in universities are adjuncts. Is it possible for most of them to teach enough classes to sustain themselves?

Also, it’s pretty messed up: all of the student debt in the world is not enough to pay all university employees a living wage.

Love is a battlefield

“Don’t reach for work-life balance,” we’re now told. The best we can hope for is work-life integration.

Some Very Spiritual People suggest that our work, itself, can be our spiritual practice.

And they’re willing to tell you all about it. You can consume a wide range of low-key bookstore bodhisattvism via thinkpieces, workshops, idk TED talks, experiences, …

It’s tempting. It’s dare I say efficient.

What could go wrong.

Thought experiment. I’ve “integrated” every domain of life; my work is my spiritual practice.

Then, my business fails. Or I get fired, I mess up a project, I fall out of favor with the powers that be, I age out of the workforce. Or whatnot, as individual effort meets structural reality.

Have I failed, spiritually, too? (What is spiritual success?)

When leaders are hell-bent on spiritual-life-work-life-integration, it doesn’t scale well. Workplace spirituality excludes. The harms of that exclusion don’t bode well for the excluded. (See Hobby Lobby.)

Personal boundaries are healthy. Including a boundary between work and personal domains.

IMO, I’m not a therapist.

I mean, may you be fortunate. Allow your spiritual life inform how you treat people. Choose work, if you can, that aligns with your beliefs. Don’t be a jerk at the office.

Before enlightenment chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment chop wood, carry water.

Zen saying

When riding the subway, on a very rare occasion, a good day, I can look around and imagine the entire universes that unfold from the lives of each of my fellow straphangers.

Mostly, though, I want to avoid manspreaders.

Sometimes, we have to act, while simultaneously holding multiple seemingly-opposing thoughts in our minds.

I feel affirmed

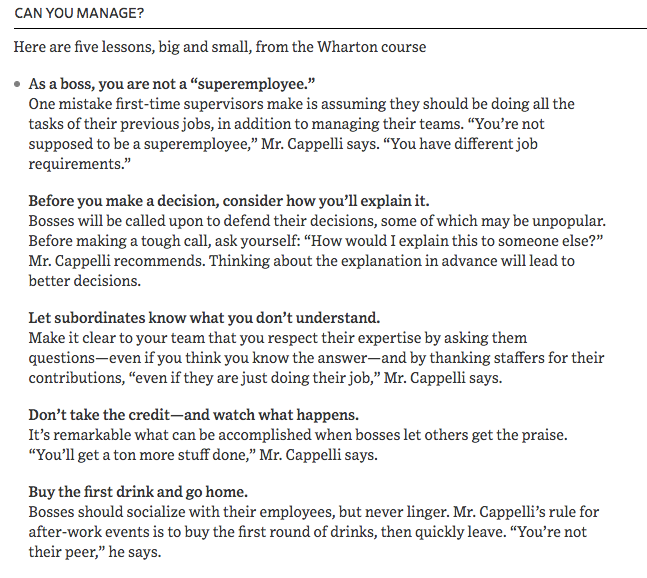

Wharton Professor Peter Cappelli is teaching a management course to undergrads (disclosure, Wharton’s my bschool alma mater.)

Back in the 90’s dot-com era, a startup CEO (a mid-career exec who should have known better) told me that management didn’t matter — the internet had changed everything.

By the 2010s, some had wised up. In 2012, I taught two courses at NYC’s General Assembly, on managing startup teams, and feedback.

I was motivated by how much unproductive and painful drama arose in new companies because people had no training, and no role models. I wanted to offer a 12-week session on people management; I wasn’t able to pitch this successfully at GA.

(PSA: hire experienced managers.)

In 2014, I visited Gary Chou. Gary had a new space, and wanted to use the space to fund the space, and was running a bootcamp for people who were launching side projects. I thought, “Maybe I can offer my program at Orbital?”

I wound up completing Gary’s bootcamp, and launching my 6-week Management Intensive program.

The need was, and is, great. Corporate America no longer has a long view on developing people managers. Startups aren’t staffed for this work, either.

Once, it would have been extremely uncommon for a new college graduate to join a startup. For one thing, startups didn’t pay well.

Today, investors like founders to be paid a living wage. (I feel like Fred Wilson has written about this?) In startup hubs there’s a competitive talent market. So employees get paid enough, too.

Today, new grads are landing in startups, and in large organizations, too. Some have never had a job. Some hiring organizations lack a cadre of experienced managers.

Once, (some) people were groomed to lead. Organizations included experienced people who modeled good (and not good) management behaviors.

If there ever was a golden age of management (which I would not claim,) it did not involve complex teams being led by people with only a few years of work experience.

Yet that’s what’s unfolding in many organizations today.

Peter Cappelli has been at the front of discussion about other structural changes in the workplace. I’m glad to see the school offering this course.

B-schools could once rely on organizations to train, mentor, and coach emerging managers. In graduate school, our classroom discussions and case studies leaned philosophical and big: you’re the CEO, and suspect your CFO of embezzlement. What would you do?

Not, “What if someone comes to work in a shirt that smells bad?” (Yes, I’ve had that conversation.)

Cappelli’s course looks like it useful preparation for the real world.

That said, I wouldn’t expect a 22-year-old Wharton grad to be an awesome manager out of the box — even a straight-A student. I would expect book-familiarity with best practices and the counterintuitive basics that trip up new managers.

The worst driver in the world can get an A on the written driver’s test: to learn to drive well, you have to actually drive.

Emerging managers will learn from leadership fender-benders and near misses.

They’ll also learn by working in environments where people management isn’t valued. Maybe the best practices are “too corporate.” PSA: if that’s your organization, they’re unlikely to stick around.

If Cappelli’s students pay attention in class, they can start off ahead of the pack. I expect other schools will follow.

How do you learn to coach your team members?

Peter Imai sent me a note after reading Always Be Coaching: On Management #36, asking if I had a favorite book on coaching.

Not really. “Coaching as a manager” is a bit shapeless. The topic isn’t neat or succinct. It’s more like a chapter in a book, rather than a whole book.

So when I think about coaching team members, I consider other domains.

Michael Lewis’ Coach: Lessons on the Game of Life is short and sweet: the audiobook comes in at under an hour. It’s about how one coach acts, and the impact of his work.

You can also find inspiration at the movies from fictional stories of coaching.

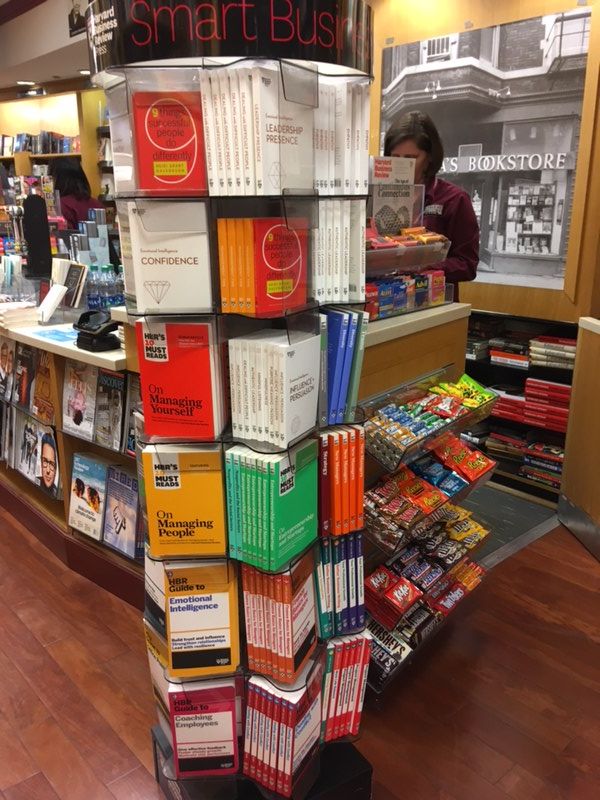

If you browse airport bookstores while traveling, you’ve probably seen the HBR guides.

Harvard Business Review has gone into its archives and created collections on management topics, ripped from the pages of the HBR.

The HBR Guide to Coaching Employees (library) (Indiebound) is a set of articles on the topic of coaching employees. After talking with Peter, I used the library* to put my hands on a copy.

To be honest, I didn’t finish it. I’ve read at least one other in the series, and skimmed several. I feel like I understand the product. I only skimmed this one, and judge it to be true to the HBR Guide brand.

I view these guides as brain food, and good ways to start understanding the shape of a topic. If you’re intrepid, you can have a similar experience browsing HBR online.

*NB: Back in the 90s I did a book purge, releasing a large stack of business books. Most were not evergreen; some were awful. I vowed to never buy a business book again. Now I (almost) always use the library for business books.

If you purchase any HBR guide to read on the plane, I won’t judge you. You’ll be well served, and you can pass it along to a friend or colleague when you’re done.

Question

What’s on your summer reading (watching, listening) list? (I’d love to know.)

Supporting Members

Thanks you so much to the people who support my newslettering financially.

Supporting members will receive a transcript of my conversation with Fobazi next week, and more:

- An experiment. Last week I started a 30 (business) day challenge, and posting one good thing I’ve read, heard, or seen that informs thinking about the workplace and managing people. Supporting Members can sign in to access them — for now, I’m not mailing them.

- A thought. I’ve been thinking of doing periodic live briefings (via Zoom) for people managers on a skill, topic or workplace trend. (Like coaching your team members.) More to come on this.

Links

- “Passion exploitation” is a thing. “…when we see someone in a bad work situation, our mind may jump to the conclusion that they must be passionate about their work. While not always factually incorrect, this may serve to legitimize instances of mistreatment,” says University of Oregon’s Troy Campbell in Love Your Job? Someone May be Taking Advantage of You at Duke University’s Fuqua Insights.

- “If adjuncts were birds, they would be fighting the drag of the air, exerting bursts of energy again and again and again.” The Death of an Adjunct, by Adam Harris at The Atlantic. See also Being an adjunct college professor can be awful by Dawn Kinnard at the Chicago Reader.

- “Resilience narratives paint workers who feel burned out or frustrated as failures who couldn’t overcome adversity.” Less Is Not More: Rejecting resilience narratives for library workers, by Meredith Farkas at American Libraries Magazines.

- Many librarians are being asked to learn to use Narcan, a overdose treatment drug that reverses the effects of opiates. What do you do when you’re not a doctor, and you don’t play one on TV — where’s the boundary between first aid and first responder? Opioid Antidote Can Save Lives, But Deciding When To Use It Can Be Challenging, by Nina Feldman at WBUR.

Jobs that crossed my (virtual) desk

- The Public Theatre is hiring a Human Resources Coordinator

- Pursuit is hiring a Director of People, Talent Acquisition Lead, and more

Dear Fobazi Ettarh — thank you. I can’t wait to see what you do in the future!

Thank you, Jason Li, for illustrating some recent editions. Hat tip to Sophie Brookover, whose retweet led me to Fobazi’s work. Thanks to my friends at Orbital and the women in my peer mentoring group for creative feedback on my work.

Thanks to the folks at one of my (two!) public libraries, where I get business (and other) books and sometimes record my audio.

Libraries are great, and yet I don’t believe that they should have to create sacred spaces or hold up our entire democracy. And I apologize for not meeting my 2019 goal to avoid incurring overdue fines: I almost made it through Q1.

And again, many thanks to Supporting Members.

Thanks to Peter Imai for asking me a question. I’d love to answer yours — please do send me a note!

Best,

P.S. ICYMI, the last few issues:

- One good thing (to read) for May 21, 2018 (a post for supporting members)

- Problematics: Members Only #10

- Always Be Coaching: On Management #36

- The rest of the archive is here.

“Uncle, please sit,” might be a new love language. Or my new love language.

And I was fine with GoT’s final episode. Fight me.