Warm Take: Performance of Care. July 25, 2021

HBO’s Generation Kill was about a bunch of US Marines in Iraq during the war. I don't remember much about it, including why I watched; maybe via a recommendation from a Marine in my circles?

What stayed with me: a scene where a lieutenant helps a private tend to his badly blistered feet. As I recall it, the captain had coached the lieutenant: if the enlisted guy can't walk, he can’t do his job; you have to help him.

Indeed, I had been similarly coached by one of my early bosses in banking, Charlie. “We take care of our people,” he always said. Charlie was a veteran, a proud grunt, and a good boss.

We were taken care of. Nice offices, subsidized lunches, cushy travel, I was given/earned opportunities for advancement. I was well compensated; the bank paid for my MBA. (It was the 90s. And yes, most of the people who received this treatment were privileged and white.)

Now, the bank's care was conditional. The care we experienced was for our metaphorically-blistered feet: what care did we need to keep doing our jobs?

That was okay with me. I had a life outside of work. I did not need work to be my family. I was okay with conditional care, with performed care. The services being provided by my job in exchange for my work were fine. (Until they weren't; I digress.)

A theme that predates the pandemic has been accelerated: that some people don't deserve for management to even pretend to care about their physical safety.

Imagine if you got assaulted on the job and your boss never called and your company stopped paying you, leaving you to fend for yourself with thousands of dollars in medical and other bills.

That’s the reality for the drivers who are paid by Lyft and Uber and who are being killed and maimed in carjackings at alarming rates, according to an investigation we published this week in The Markup.

Julia Angwin, in The Markup’s "Hello World" newsletter, July 24, 2021

The New York Times is at its best when veteran reporters dive deep. Investigating Amazon, the Employer is filled with gems about the lack of care for humanity, managers who manage unwieldly numbers of people under impossible conditions, and more.

Here, Ann Castillo's husband is gravely ill. She is unable to work with Amazon to access his benefits.

For months, Ms. Castillo, a polite, get-it-done physical therapist, had been alerting the company that her husband, who had been proud to work for the retail giant, was severely ill. The responses were disjointed and confusing. Emails and calls to Amazon’s automated systems often dead-ended. The company’s benefits were generous, but she had been left panicking as disability payments mysteriously halted. She managed to speak to several human resources workers, one of whom reinstated the payments, but after that, the dialogue mostly reverted to phone trees, auto-replies and voice mail messages on her husband’s phone asking if he was coming back.

You know, for years I've been talking about what it takes to manage people. At its core, it's when we act with the humanity of others in mind.

This isn't what's happening with the Uber and Lyft drivers, or the Amazon workers described by the NYT.

It chills me to think that we -- as a society -- want to live in a world where only an elite cadre have access to a performance of care.

Unless we like this development, it's on us to find whatever power we can to push back against the forces that don't want to care for human beings who are doing the work.

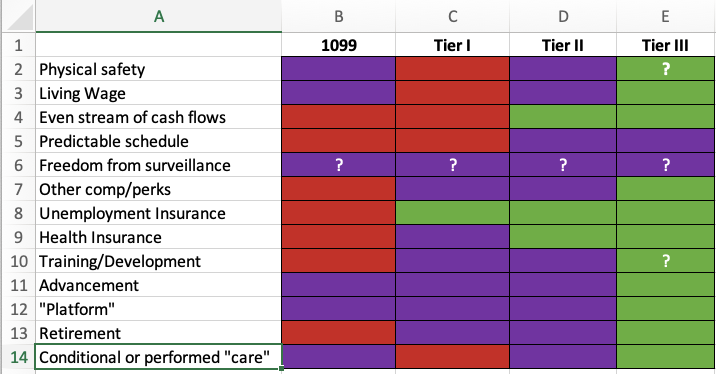

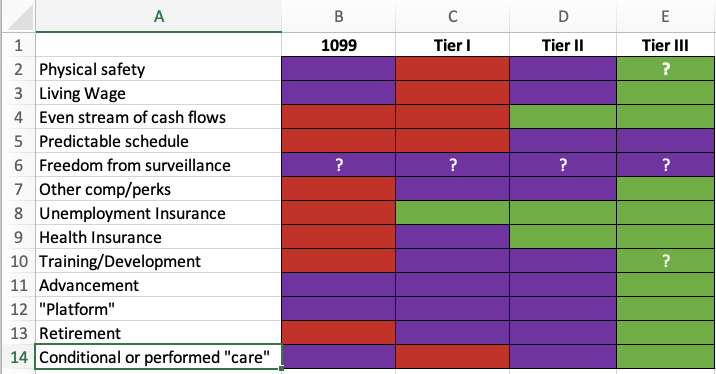

Today I updated my “job as a service” grid, adding conditional/performed care as a service.

Green represents a service provided; red is the opposite. Purple is, "it's complicated." As this is a Warm Take, I won't dive into my informal model for the different services provided by jobs to people in different classes of employment. (There's more in Information supply chain, interrupted: Members Only #15). And I'll come back to this.

I unpaywalled this post in April, 2022. It went out to Supporters in July 2021.

This Warm Take was complete before noon, though mailed slightly later. I'm loaded for bear and still on my second coffee; there will be typos. I will fix them later, on the Internet.

If you're still reading, I would ask you to see if you can access the full archive, including paywalled articles. The transition from Substack has been super bumpy, and I'm not sure that the archive works correctly. Here's Information supply chain, interrupted: Members Only #15, which I referenced earlier. If you can do me a favor, and let me know if the link does not take you to the article, I'd appreciate it.

Thank you so much for being a financial supporter of On Management. It's a compliment to me when you share it with a friend.

May you and your loved ones be safe, healthy, and free.

And now, my entry in French Dispatch meme annals. NB: Pretty sure I'm not as funny as I think I am.

(Ok, probably only 16 people would find this funny.)