Ready for your intervention? On Management #38

Change is hard. Many change initiatives fall short or fail.

What questions should we ask about change? What if we need to change the way we think about changing?

This month’s audio features Jane Watson, who’s spearheading an innovative exploration of workplace sexual harassment in Toronto Tech — because it’s clear that standard interventions meant to combat harassment simply aren’t working.

Thank you for inviting me to your in-box.

State College

So, you want something to change in your workplace.

Merriam-Webster defines intervention as the act of interfering with the outcome or course, especially of a condition or process (as to prevent harm or improve functioning.

When we seek change at work, we often jump into action. We find someone to run a workshop, send someone for training, buy software.

By adding an intervention, we hope to buy a change in state.

This is the ready, fire, aim approach.

Earlier in this century, I talked with two teammates who were interested in a team-building offsite.

One told me about some of the team’s issues and concerns. The other said that he didn’t want to discuss their problems: they wanted someone who would facilitate a fun day of team-building.

Because they didn’t agree, I didn’t feel I was the person to design a useful day for them — at least not within their budget constraints. We all moved on.

Since then, I’ve learned to ask: what do you wish to transform?

An effective intervention can initiate a change in state, or support one. The intervention is not the solution.

Someone in my circle talks about her work with “Kevin the Trainer.”

Kevin sets up a workout plan, shows up for appointments, helps her to track progress.

His scope is limited. Kevin can’t drive her to the gym. Swing the kettlebells. Refuse the second cookie.

Hiring Kevin was only part of her work. First, she decided on a desired change in state: she wanted to be in better health.

Then, she chose the intervention. To be clear, Kevin, himself was not the intervention: her work with Kevin was the intervention.

She does the work, herself.

There’s a lot more going on in our workplaces. After drilling down on what must change, any intervention needs to be designed to fit your situation.

You’ll need to help participants to prepare, and let them know what you expect from them.

Afterwards, you may need to re-arrange processes to enable people to practice what they’ve learned.

You may need to show up differently at work, and question how your relationships operate.

You may need to change the way you do your job, as a leader, to reinforce what you wanted people to learn. Maybe even change the way you spend your own days.

You can’t buy the change you wish to see in the world. You must be that change, yourself.

It’s not working

The small progress we’ve made since then has not been enough.

Despite mandatory trainings, reporting hotlines, and even whisper networks, our interventions have had disappointing, possibly damaging, results.

The Toronto Tech Study is an innovative approach to exploring workplace sexual harassment.

Instead of crafting a new solution, Jane Watson, Eleanor Snowden and Anna Hanchar are spearheading this study, a collaboration between The Aperta Project and the Cynefin Centre.

Jane joined me to talk about the study. I hope you’ll enjoy our conversation, which I’ve edited for length and clarity.

If you're part of Toronto tech and want to participate, the study will be open until August 24. Click here to add your voice.

If you know someone in Toronto Tech, please do send them a link to the study: theapertaproject.com/study.

Jane Watson is a Toronto-based HR professional with experience in startups, not-for-profits, and public companies, and founder of The Aperta Project. Jane writes about people, culture, and work, at Talent Vanguard.

It’s complicated — or is that, really, it?

Here’s a brief video intro to the analytical framework Jane mentioned in the audio.

Jane and I discussed unintended downsides of a purely compliance-based response to harassment reports. That said, if you’re responsible for your organization’s response to harassment, you’d better respond.

Lisa Guerin’s The Essential Guide to Workplace Investigations: A Step-By-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & Problems (July 2019, 5th edition) (Indiebound) (library) is a solid reference guide for HR professionals and managers. Kids please don’t try this at home: talk with an attorney.

If you’ve been a target of harassment, you’ll find resources at the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund.

Another questionable intervention

Back in the 90s, my bschool study group did a consulting engagement as a class project.

We were invited into an old-school Fortune 500 industrial company. The problem: “Diversity.” One intervention we looked at: a mentoring program.

I don’t remember our conclusions.

Since then, I’ve seen a bunch of mentoring programs, and participated in a few. Some were mediocre.

This includes my own experience in a volunteer-staffed tech industry group. One year I was a mentor; the next, I joined the committee that led the mentoring program.

It’s difficult to measure our impact: before the program even ended, the committee chair stopped calling meetings and responding to emails. And that was the last I heard of it. Volunteer-led efforts can be messy.

Looking for a counter-example, I asked around, “Who out there has cracked the code on formal mentoring programs? Are they in a company? A not-for-profit? Government? (Do they exist?)”

The response was not overwhelming.

To be clear, mentoring is an age-old way of learning. And I’ve been so fortunate to have been mentored by some masterful managers and coaches. These relationships arose through existing relationships, not from a program — not from an intervention.

Observation: some individuals have great experiences in formal mentoring programs. Overall, the programs haven’t driven systemic change.

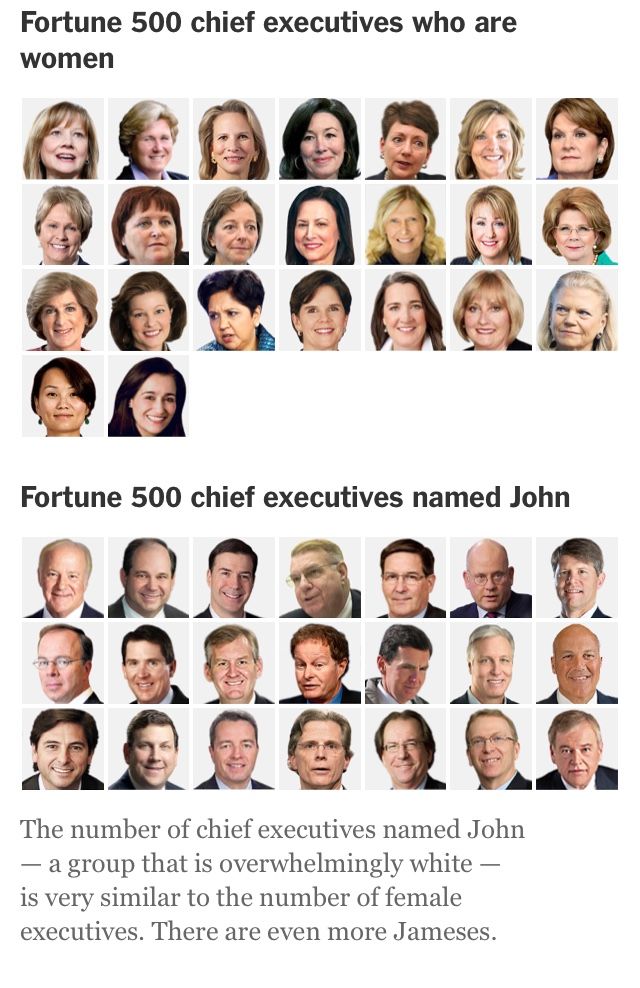

Witness the ranks of female Fortune 500 CEOs, circa spring 2018. And, their peers who are named John.

I’d wager that companies led by these women have been running mentoring programs for a generation. Or more.

When female Fortune 500 CEOs are outnumbered by (white) male CEOs named John, one obvious goal of hundreds of mentoring programs has not been met.

The NY Times also points out, “There are even more Jameses.”

Many of the CEOs pictured are contemporaries of women my study group interviewed back in the 90s.

Today, that company is a subsidiary of a Fortune 100 company.

The CEO’s name is Jim.

A question

What actions are you taking to identify what must change?

Get out!

A couple of years back I wrote about indicators of problems inside an organization. Whether you’re the CEO, or a team leader, it’s stuff you should watch for — and act on.

When your organization has problems, people generally try to tell you.

If only you’ll listen.

Some people are direct. They ask pointed questions in your all-hands. Complain to HR. Offer lackluster responses to employee surveys.

When your actions fail to show that you’ve heard them, some quit. Some stay, and start sharing stories outside of your organization. I’ve called this leakage.

Some reach out for revenge (negative Glassdoor review) or reparations (legal action.)

Increasingly, I’m seeing something I’ve been calling “managing out.”

These folks don’t want to leave. They’ve tried to tell you. You haven’t acted on their concerns. So they look outwards for help and support.

Sometimes, they look to the media. Media strategies include rage-tweeting about management, speaking to reporters off-the-record, and actively courting media attention.

At Nike, a group of female executives “covertly…surveyed their female peers, inquiring whether they had been the victim of sexual harassment and gender discrimination.” The survey landed on the CEO’s desk, and was followed by an “exodus” of male executives.

Wall Street Journal reporting delved into an informal summit held by senior women to discuss bias they’d experienced at Wells Fargo; at least one senior male executive exited shortly afterwards.

Based on deeply reported and sourced stories by The NY Times and WSJ, my hypothesis is that media pressure came to bear at both Nike and Wells Fargo.

Managing out is a political action, one with an uncertain outcome. Some who manage out get burned.

The Google Walkout was visible to the outside world, and fueled by social media. And, it was followed by resignations and claims of management retribution.

And, in politics itself?

The U.S. Congress is a very different workplace than most of us will ever experience. Managing out is part of politics; consequences are different than what most will experience in our workforces.

The Squad is indeed more than 4 people, and that’s part of the difference: our workplace squads don’t — strictly speaking — vote us into our jobs.

Can a “rage tweet about management” story end well, employment-wise?

By the time your employees start managing out, your concerns will include calculating how media attention affects your ability to retain employees and recruit people.

In two of my past audio segments, Jane Watson and Juliette Austin have both invoked “curiosity” and “humility” as useful qualities to bring to our evaluation of tough problems we’re faced with at work.

When people bring you problems they perceive at work, your own curiosity and humility are an ounce of prevention. When you listen, well, fewer people will feel compelled to manage out.

very proud of this meme i made today pic.twitter.com/EEzELaGhC2

— dr. kpan (@panacirema) June 13, 2019

Remember Bobby Knight?

Over the last few months, I’ve been hearing about Trillion Dollar Coach, which I’ve been dragging my feet on reading

It’s about Bill Campbell. Campbell was a college football coach who became an executive and board member at a number of tech companies. He’s known for having coached a number of Silicon Valley execs, and delivering tough news that helped them to improve their performance.

When you want someone’s performance to change, you’ve got to tell them the truth. Good managers coach people.

However, the way you deliver tough news, well, it depends.

Every person who works for you is different. When you give people the truth so that they hear it, and can take action, that’s the art.

Joe might be acting like a jerk. And so might Jane. Jane might just need to hear, “You’re being a jerk.” Given the same feedback, Joe might fall apart.

You don’t need to act tough. Make people cry. Or throw a chair.

People will hear tough feedback when you meet them where they are. Pro-tip: bring the truth with you.

When you’re going to work with someone — your next manager, Kevin the Trainer, or an executive coach — they must learn “where you are” so that they can meet you there. How will they do this?

That’s a question to ask. The intervention is not the solution.

And the person is not the intervention. You must do the work.

Books, Books, Books!

Cathy Pisano won my somewhat random book drawing. From a few options, Cathy chose The First 90 Days: Proven Strategies for Getting up to Speed Faster and Smarter (Indiebound) (library).

Every manager could use this book to reverse-engineer actions required to support your new hires from before Day 1.

Thanks, Cathy!

If you’re not in it…

I’m giving away a paperback copy of CV Harquail’s Feminism: A Key Idea for Business and Society (Indiebound) (library).

CV will join me in September for a Q&A about her book. Want to join this conversation? Please let me know.

When you enter the drawing, I’ll mail you a postcard with a book recommendation. A real postcard. My recommendation might be a bit out of the box.

Disclosures

Jane Watson and CV Harquail are both supporting members of On Management. CV’s wisdom has appeared in past issues of the newsletter, long before supporting membership existed. Jane was the first person I didn’t know (at the time) who signed up to be a supporting member.

Finally, none of the links in this newsletter are affiliate links. Once upon a time, I used Amazon affiliate links, some of which persist in my older stuff on the internet. As I happen across them, I am removing them.

Supporting Members

Thanks you so much to the people who support my newslettering financially.

If you’d like to chat with me 1:1 on August 15, Office Hours are ON, dog days of August be darned.

Supporting members will receive a transcript of my conversation with Jane in the next week or so.

If you’re hard of hearing or Deaf, send me a note and I’ll add you to the distribution for the transcript.

Links

- Ross Gay’s “Loitering,” via “Ross Gay: Tending Joy and Practicing Delight,” on On Being with Krista Tippet.

- How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, by Jenny Odell. (Indiebound) (library). An interview with Jenny on The Longform Podcast led me to this book.

- Quartz Obsession is often delightful. Here’s one I liked: Boredom.

- “What did Mr. Carcia learn from his experience? ‘I need people,’ he said.” Worcester hiker Philip Carcia completes White Mountain challenge in record time, by Susan Spencer of the Worcester Telegram & Gazette. (h/t Appalachian Mountain Club)

Many thanks to Jane Watson for taking time to make this audio with me, and to LiJia Gong who tipped me off to the impressive scope of services offered by the TIME’S UP Legal Defense Fund.

Thank you for reading. Thanks to supporting members, for your financial support of the newsletter.

Enjoy the rest of your summer. I’ll be back in a few weeks with a P.S. to this issue.

ICYMI

- So I've been thinking: Members Only #11 (supporting members)

- On Management #37, P.S.

- I liked Late Night. Fight me. OGT, June 21, 2019 (supporting members)

- Minimum Viable Passion: On Management #37

Gen-X entertainment mood: eeeeew.

It’s astonishing that we didn’t see how truly gross this film was when we were young. I guess I’ll call this progress.