Platforms: On Management #45

My first email newsletter went out around 1996. One of my closest friends called it “Anne’s Zine.”

Today, here’s a very zine-y, long issue. If it’s truncated in your inbox, you may click here and read it online.

Thank you for inviting me to your in-box.

10/19/20 update: If you’re reading on the web, after the email went out, I corrected two or three typos, made one edit for clarity, and fixed a couple of clumsy sentences. It’s still imperfect.

Verbing a noun

Some years ago, while pondering the elements of the workplace social contract, I made a drawing.

My drawing was about Job as a Service. The unbundling of employment. (I love Ben Thompson’s drawings!)

One of the elements that I added to the drawing: platform. As both a noun, and a verb.

As I see it, platform, the noun, can be a software entity that enables ostensibly frictionless interactions, transactions, brand-building and “entrepreneurship.”

Platform, the noun, can also mean “audience.” So, if you write a book, publishers want you to have a platform, to prove that your book will sell.

Next, deplatform, the verb. It’s what happens, for example, in rare cases when someone dangerous is kicked off of Twitter.

Does de-platform have an antonym: to platform?

I say yes. It’s when an organization or institution puts someone in a position that conveys visibility, access, credibility, authority, and/or power.

It’s different from sponsorship. You have a sponsor when a powerful individual deploys their political and relationship capital to offer you visibility, access, credibility, authority, and/or power.

Example: someone is pounding on my door. I look out to see 240-pound white dude in street clothes. When he yells, “Open up,” I might look for my escape route.

If the same yelling man is wearing bunker gear, and I see a ladder truck outside my house, I’m going to open the door.

The FDNY platforms this man. As employers platform (some) people.

Here’s a current narrative about the future of work: “Everyone should/will be an entrepreneur.” That everyone should/will build our own platforms.

That we can platform ourselves.

I’m not here today to address every flaw in that position.

But I am so here to talk about some of the financial value of being platformed, or not.

I sold my soul to the company store

Yessir, there's a-many a Kentucky coal miner that pretty near owes his soul to the company store. He gets so far in debt to the coal company he's a-workin' fer that he goes on fer years without being paid one red cent in real honest-to-goodness money. But he can always go to the company store and draw flickers or scrip -- you know, that's little brass coins that you can't spend nowhere only at the company store. So they add that against his account and every day he gets a little farther in debt…

Merle Travis, spoken word intro to “Sixteen Tons,” transcribed by HuesosBrigada

I legit woke up at 4am one day with an earworm: “Sixteen Tons.”

Instead of trying to sleep, I fell into a hole on the internet. The song has some deep history, and has been covered and discussed by the likes of Johnny Cash, East Bay Ray (ex-Dead Kennedys) and Tim Armstrong (ex-Rancid.)

My mental cover of “Sixteen Tons” didn’t emerge from some random dream shuffle. It's about early 20th century coal miners, who worked in conditions that we could have left behind.

Influencing my mental playlist: the unbundling of employment. Platforms that extract financial value from workers. The so-called future of work.

And I was thinking about one of the software platforms, Netflix, and investor Andrew Walker’s blog post on what he called Netflix’s “moat,” which I recently saw more than once on Twitter.

…The bottom line is Netflix can turn just about anything into a cultural hit by putting it on the front page of their website.*

Warren Buffet uses moat to mean a distinctive competitive advantage, something that enables a company to charge a premium price, or command outsized market share.

Walker was talking about the moat’s value a bit differently.

That's a mammoth edge; over time, they should be able to hire the best talent and the best shows for less than competitors because of that edge.*

So, um, Netflix “should be able to” extract value from “the best talent.”

Look at Sandra Bullock's imdb page; she's had precisely one relevant project over the past ~7 years and that was Bird Box (Netflix). Or consider Drew Barrymore; Santa Clara Diet is probably the only relevant thing she's done in the past decade. Why couldn't Netflix go to the "next" Sandra Bullock / Drew Barrymore and say "make this movie for us for free and we'll make you relevant again?" If Sandra Bullock doesn't do anything relevant for another five years, would she pay Netflix to star in a Bird Box sequel or some other vehicle to regain some attention?*

You may laugh, but why wouldn't a washed up star pay $100k to star in a movie that they know 40m people are going to watch? That would be the best investment of their life; I guarantee you they could make 100x that money from the increased attention (new sponsored products, selling stuff on their instagram / twitter to their increased follower count, making more money in their next roll (sic) now that they're in demand again).*

So, members of a “washed up” Hollywood underclass should pay Netflix to work.

For the record, I’m not laughing.

And, who’s washed up? Would you shut up and check Wikipedia, man?

OK, so who else should pay to to be on a (so-called) platform?

How about customer service agents, employed (kind of) by Arise Virtual Solutions.

Arise’s workers not only don’t work for its clients, they also don’t officially work for Arise. Like Uber drivers or TaskRabbit gofers, they are independent contractors. To get gigs, they first absorb substantial expense, paying for their own equipment and training, and then have fees deducted from every paycheck for the “use” of Arise’s “platform.”

Meet the Customer Service Reps for Disney and Airbnb Who Have to Pay to Talk to You, by Ken Armstrong, Justin Elliott and Ariana Tobin at ProPublica.

This arrangement has a distinct multi-level marketing scent.

- Reps are recruited via social media and social ties (yikes, their churches?!)

- “Entrepreneurs” may do significant unpaid work during training.

- Once someone has invested time and money, there may be no demand for their services.

Customer service roles were once solid entry-level jobs; I know a number of mid-career executives whose careers started in CS.

Today, where does this job — I mean gig — lead?

One road takes us straight back to the old-school company store.

*from Some things and ideas: September 2020, at Yet Another Value Blog, by Andrew Walker

Unbundling Employment

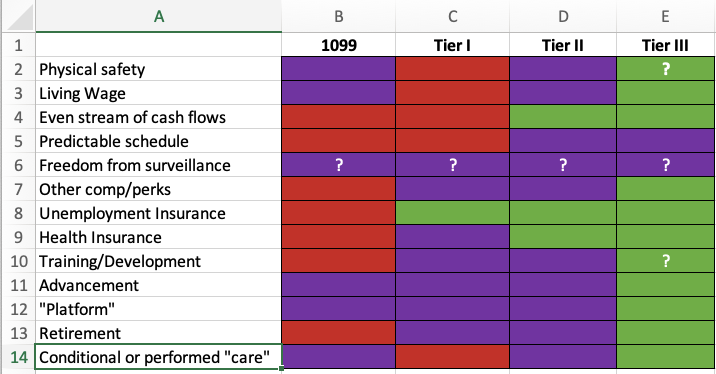

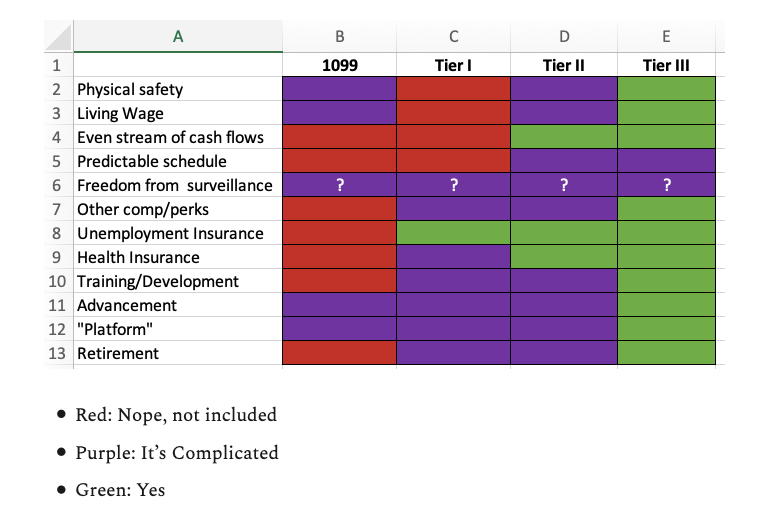

Earlier this year, seeking to make sense of the post-WWII job bundle, and its benefits, I made a table and shared it with supporting members of On Management.

A call center agent’s job once existed in my Tier III — with benefits and a regular schedule. Companies like Arise and their clients are normalizing a shift to a status that offers fewer protections and benefits.

When we’re fortunate, we have some choices. The organizations we decide to work for, or buy from. Decisions we make at work, and about how we work.

The laws we’re willing to live with. And how we vote.

Proposition 22 is on the California ballot in November. If enacted, it will split 1099 workers into more than one category, with different protections under the law.

Like me, some 1099 workers run one-person businesses that are not core elements of our clients’ businesses. We have significant autonomy over our work.

Other 1099 workers are managed by an algorithm, and they’re paying to work.

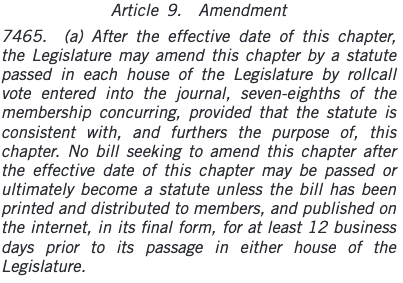

A chilling element of Prop 22, buried in nearly 10 pages of fine print, is that any amendment will require agreement by 7/8 of the legislature.

In my view, laws like Proposition 22 seek to divide the interests of people like me from the interests of Uber drivers. And who wins?

Make no mistake: someone probably wants to treat you as a contractor.

Vote.

Platformed

When a company receives funding from a prominent institutional investor, they also gain credibility that can attract press, talent, and of course additional money.

They’ve been platformed.

Last summer, I saw one of the first critical business analyses of WeWork. Writing at NY Magazine, Reeves Wiedeman offered a back-of-the-envelope valuation that made sense to me. Since then, WeWork crashed, and Covid hit.

Wiedeman’s Billion Dollar Loser: The Epic Rise and Spectacular Fall of Adam Neumann and WeWork (Bookshop) (library) comes out this week.

It’s a history, timeline style, of WeWork’s journey from scrappy 2-man shop, to the largest commercial tenant in NYC, to failed IPO. And, a lot of drama.

Because I had followed WeWork closely — the summer camp, the beer, and SO MUCH CONSCIOUSNESS — some of Wiedeman’s tale was familiar.

The color commentary, um wow. I read the book and kept notes on an e-reader.

WTF. Neumann tells Bush-era national security advisor Stephen Hadley that Saudi prince Mohammed bin Salman needed a mentor. “When Hadley asked who that might be, Adam paused, and then replied, ‘Me.’ ”

Lol. WeWork led a $32 million investment in surfer Laird Hamilton’s nutritional coffee creamer company.*

Yikes. Ashton Kutcher brainstorm: surveil WeWork visitor logs to see which client companies had high-profile visitors; use this info to assess company potential.

Near the end of the book, I started adding the note “Ponzi.”

This month, my book club read The Glass Hotel (Bookshop) (library). Emily St. John Mandel’s story circles a Bernie Madoff-inspired character, Jonathan Akalaitis.

When book club met, our views diverged widely. I was surprised by our lively discussion about Akalaitis’ intentions. Did he start out as a con artist?

Maybe he was a legitimate investor, who used false data to paper over a big loss — only to find that he could never catch up with his lies. So, enabled by people who were dependent on believing his story, he dug himself into an ever-deeper hole.

WeWork is a real company; nobody thinks it’s a Ponzi scheme.

However, Wiedeman describes several financing events; when new money came in, some investors cashed out at valuations that haven’t stood up.

Like Travis Kalanick, and Elizabeth Holmes — and other less-controversial figures — Adam Neumann was platformed in a way that was not congruent with his track record.

A moral of Billion Dollar Loser: being platformed and force-fed money does not always add up to a successful enterprise.

And, this story is not over yet.

*And, also lol, in September 2020, Laird Superfood went public at a $40.80/share — as I write stock is trading at $48.84; who knows where it will go from here. (At the September 1, 2023 market close, the stock price was $1.02/share, market cap was $9.3 million.)

Question(s)

Who are your organization’s outsource and contract workers; how do their interests and benefits differ from yours?

Links

Paying (a platform) to play

- Meet the Customer Service Reps for Disney and Airbnb Who Have to Pay to Talk to You, by Ken Armstrong, Justin Elliott and Ariana Tobin at Propublica.

- Call Center Call Out, by Amanda Aronczyk and Ariana Tobin (audio) at Planet Money.

Platforms are people too

- Excellent Prop 22 explainer from the Los Angeles Times.

- Uber and Lyft Are on the Ballot This Election, by Eric J. Savitz at Barrons says that Uber, Lyft, Instacart, Doordash and Postmates have spent $180 million on Proposition 22.

- This Could Change Everything (w/ Veena Dubal), Maximillian Alvarez talks with Veena Dubal about Proposition 22 at his Working People podcast.

Deplatformed

Jessica Bruder’s Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century (Bookshop) (library) is about the grinding existence of itinerant Americans riding out the post-2008 financial crisis in RVs, vans, and cars. Under the CamperForce brand, Amazon found a way to market warehouse jobs to this community. (Of course they did.)

Nomadland comes to the big screen in December.

Something something — platform — throwing my hands up in the air

Several people sent me Journalists Are Leaving the Noisy Internet for Your Email Inbox. Mostly people who have seen my evolving deck: 15-20 slides of financial and market analysis of the newsletter landscape.

The article describes how Substack, heretofore a software platform, “has started behaving more like a publisher, offering editing help, health insurance and access to Getty Images photographs to some writers.” At this point, “some writers” would seem to mean writers who bring large platforms to the Substack platform (lol.)

Substack says they aspire to serve a “healthy free press.” In my view, they’re seeking to rebundle a media workplace — only, the workers are “independent,” and paying fees to Substack and Stripe.

- Related: in an expansive Longform Podcast interview, Barton Gellman shares his calculation of the downside of breaking the Edward Snowdon story as a freelancer, and subsequent decision to return to The Washington Post.

I’ll be there

I enjoyed talking with Donna White about leadership and managing people. You can sign up here to join us!

Disclosure: I received a (free) advance copy of Billion Dollar Loser. Also, links in this email are not affiliate links.

Many thanks to the members (sponsors) who lend financial support to On Management (my platform, lol.)

I’m early-voting this week. US readers, what’s your voting plan?

May you and your loved ones be safe, healthy, and free.

Washed up, indeed.